History of Ashland's Water System

The original inhabitants of Ashland included the Shasta, Takelma, and Latgawa people, in particular the Ikirakutsum Band of the Shasta Nation. They called the area where the current Ashland City Plaza resides K'wakhakha, "Where the crow lights". European settlers forcibly removed these indigenous people, and created the town of Ashland Mills sometime in the 1850s. For the next 30 years, lumber and flour mills popped all over the valley. Water-powered mills sprung up around what today is Ashland's Lithia Park, as well as along Neil Creek just south of town, as water became a critical resource for both firefighting and commerce. By 1871, Ashland officially became a town and built a US post office, deciding to drop "Mills" from the name to become simply Ashland.

Before Ashland formalized a drinking water water system, a private electricity generation business was set up in 1886, forming the Ashland Electric Power and Light Company. They obtained important water rights from Ashland Creek and built the city's first hydroelectrical generator near the entrance of today's Lithia Park. Ashland's first electric light was turned on in 1889, 10 years after Thomas Edison invented it. But the company was relatively short-lived, and by 1906, the company's holdings were turned over to the City after several years of litigation.

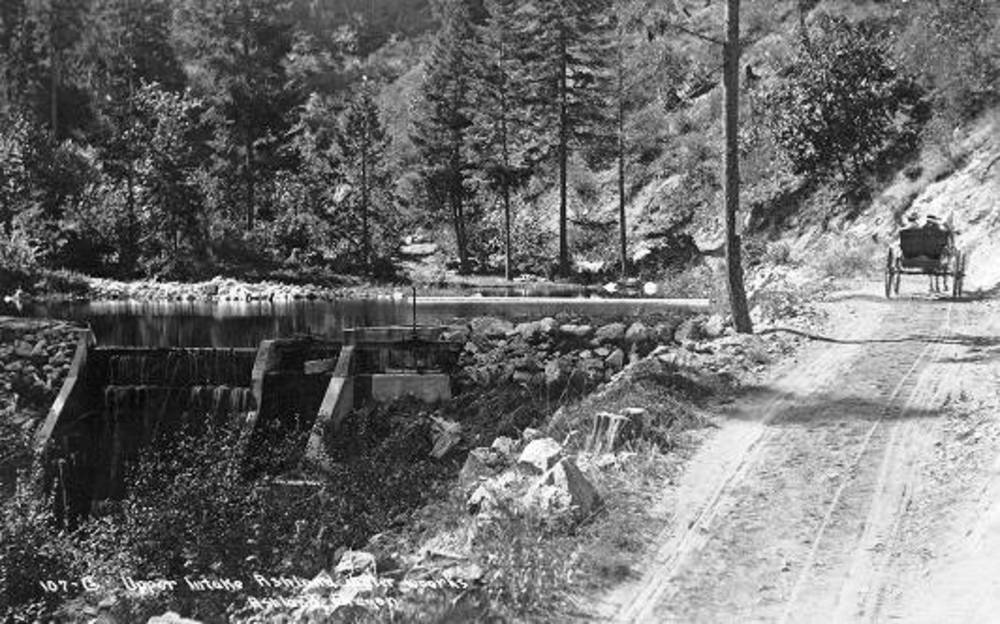

In 1887, Ashland built its first water system, ostensibly for fire protection, not just drinking water. A year later, Medford began diverting water from Bear Creek through an open ditch to help service their growing municipal needs as well. By 1891, Ashland's city council petitioned the federal government to protect the entire Ashland Watershed to protect it from "timber land speculators and other types of vandals." Two years later, the Ashland Forest Reserve was proclaimed, protecting 1 of only 2 municipal watersheds in Oregon. Within 2 years, Ashland was also beginning to think about protecting its water supply, even if it hadn't already built a water system.

In the early 1900s, cities in the Rogue Valley began to realize they needed to formalize and organize their water systems with more than ditches, and they had to figure out how to pay for them. Between 1897 and 1902, the Fish Lake Water Company was bringing water into the valley from outside sources, including Bear Creek, Little Butte Creek, and Fish Lake.

Between 1906 and 1908, the City of Ashland took charge of the Ashland Electric Power and Light Company, including its water rights, ditches, power plant, and land. As the need for electricity grew, the City of Ashland installed its own 300-kilowatt hydroelectric plant in 1908 on Ashland Creek above Lithia Park. By 1915, Ashland's municipal electrical utility was established as a public utility, and electricity demand was quickly outstretching supply.

Between 1915 and 1928, when Ashland built Hosler Dam at the confluence of the West and East Forks of Ashland Creek, there was a mad scramble to formalize municipal water systems all over Southern Oregon. Hosler Dam created Reeder Reservoir, which provides 280 million gallons (MG) of storage for the City’s water supply. This is roughly a 1 month supply of water for the entire city, at minimal usage levels. In 1948, the City built its current water treatment plant (WTP), just below Hosler Dam, in a steep, narrow gorge of Ashland Creek. The location choice served a dual purpose in providing good hydroelectric potential, as well as just enough room for a water treatment plant rated at 7 million gallons of water per day (7MG). Ironically, within 2 decades, Ashland outgrew the capacity of this tiny hydroelectric facility. For several decades beginning in the 1960s, the hydroelectric generation at the WTP was halted because the City was tied into regional and statewide delivery systems and needed far more electricity.

In 1967, Ashland experienced the biggest flood since European settlement, disrupting water delivery to customers for a month. This became the high water mark for Ashland Creek, however, the 1997 New Year's Day flood also caused significant damage and 2 weeks without tap water for Ashland residents. Over the next decade, it became clear that additional water planning needed to be done to address the significant dangers to the city's WTP from flooding and rock slides, and to increase the city's water sources from dependence on Ashland Creek. In addition, it became painfully obvious that Ashland's water storage system ran dangerously low during peak summer months, severely impacting the ability to effectively fight wildfires around the city. A backlog of pipes at the end of their useful life from Ashland's already aging water infrastructure was also documented.

On Aug 9, 2010, a team of climate specialists from the University of Washington finalized a report to the City of Ashland regarding climate change. Based on widely accepted climate models at the time, the report made a conservative estimate of extreme situations Ashland could expect within the next 50 years. Unfortunately, the key drought prediction came true within 5 years, and Mt. Ashland saw so little snow for 2 years that it could not open its ski resort for any significant public time.

In April, 2012, a new, state-mandated Comprehensive Water Master Plan was adopted by City Council. The 50-year climate extremes predicted to affect Ashland came true within 5 years, illustrating the need for effective strategies to combat climate change. In the same year, water revenue was in the red, with city water services costing $160K more than city water fees collected. This was a significant improvement over the prior year. The total cost of the recommended improvements in the Plan totalled $30.6 million ($35.5 million inflated to the time of construction).

Today, the City of Ashland has 3 distinct sources of drinking water supply, each from a different watershed: Ashland Creek, the TID, and the TAP Intertie. The TID water originates in the Cascades from Hyatt and Howard Prairie Reservoirs, while the TAP Intertie provides treated water from the Medford Water Commission's Lost Creek Lake. The TAP was originally designed to be an emergency supply, but has since been used to supplement drinking water supply in the Granite Street system to relieve stress on the system. Water from the TAP can not currently be pumped to other portions of Ashland. The water treatment plant is rated at 7.5 MGD (million gallons per day) or 5067 GPM (gallons per minute. The TAP system can provide 2.13 MGD or 1480 GPM. The distribution system includes over 70 miles of water lines, 5 pump stations, 29 pressure reducing stations, 925 fire hydrants, and over 6700 individual services and meters. The Public Works Department is responsible for new service installations, main line construction, and the maintenance and repair of the existing system.